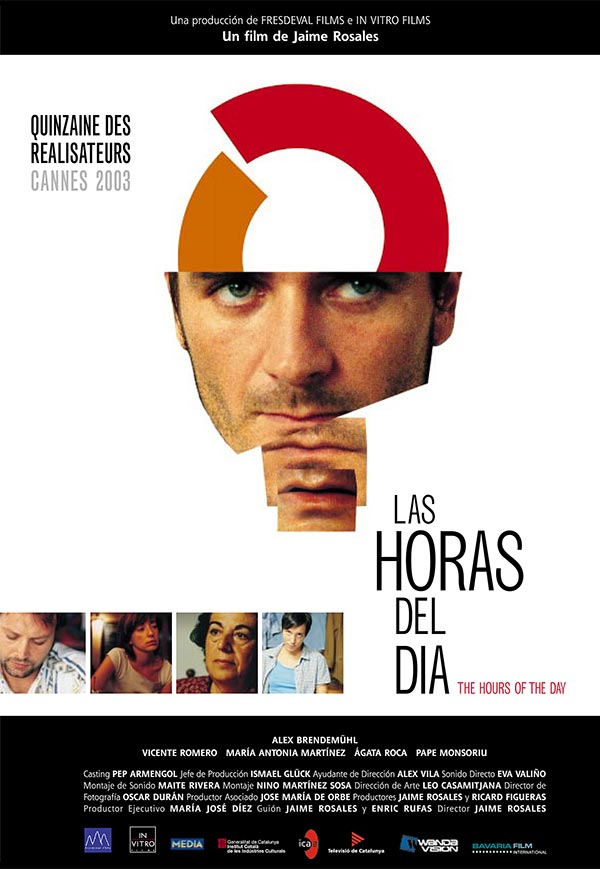

The Hours of the Day

Jaime Rosales

2003

Synopsis

Abel lives with his mother in a small town in the outskirts of Barcelona. His whole life revolves around their small family business, his mother’s house, his girlfriend’s bed, the corner newsstand, and the neighbourhood bars and cafés. It’s always more of the same: the same old problems, same faces, and the same old conversations. However, under his pleasant, calm exterior, something inexplicably cracks apart, and does so repeatedly. He is powerless to stop it.

One Thursday afternoon, Abel commits another murder.

TECHNICAL DATA

Original Title: LAS HORAS DEL DÍA

Year: 2003

Director: Jaime Rosales

Country: España

Format: 35mm, color, 1:1,37 Dolby

Length: 101 min

Language: Spanish

Shooting Locations: El Prat de Llobregat and Barcelona

Production Companies:

Fresdeval Films (Spain)

In Vitro Films (Spain)

With the support of:

MEDIA

ICEC (Generalitat de Catalunya)

ICAA (Ministerio de Cultura)

TVC (Televisió de Catalunya)

Canal +

RTVE (Televisión Española)

World Sales: Bavaria Film International

Distribution in Spain: Wanda Vision

INTERNATIONAL PREMIERE

Director’s Fortnight, Cannes 2003, Premio FIPRESCI

NATIONAL PREMIERE

6 June 2003

AWARDS

FIPRESCI prize at the Director’s Fortnight in Cannes 2003

European Film Academy nomination for Best First Film (Fassbinder Prize)

2 Spanish Academy nominations (Goyas) for Best First Film and Best Original Screenplay

Best Director Tudela Film Festival

Best Film Albacete Film Festival

Best First Time Director by the Spanish Critic’s Society (ADIRCE)

Best First Time Director and Best Actor (Alex Brendemühl) by the Catalan Director’s Society (Barcelona Prize 2003)

Best Film by the Catalan Critic’s Society

Best Spanish Film Estepona Fantastic Film Festival

Jury Prize winner Buenos Aires Independent Film Festival (BAICI)

OTHER FESTIVALS

2003

TORONTO IFF

EDIMBURGO IFF

PUSAN IFF

CHICAGO IFF

BOGOTA IFF

LA HABANA IFF

HOF IFF

2004

ROTTERDAM IFF

MIAMI IFF

SAN FRANCISCO IFF

BUENOS AIRES IFF

KARLOVY VARY IFF

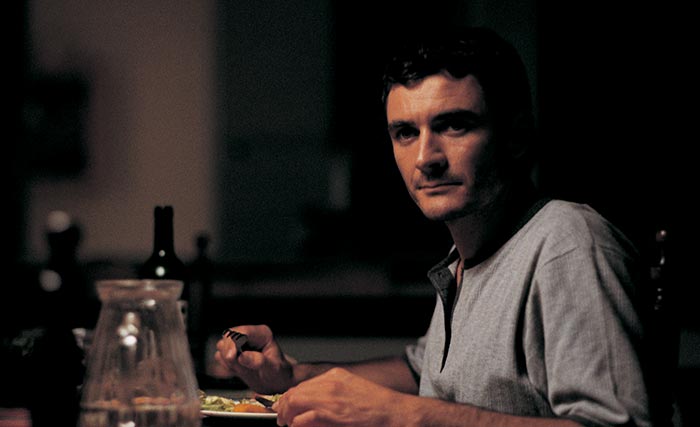

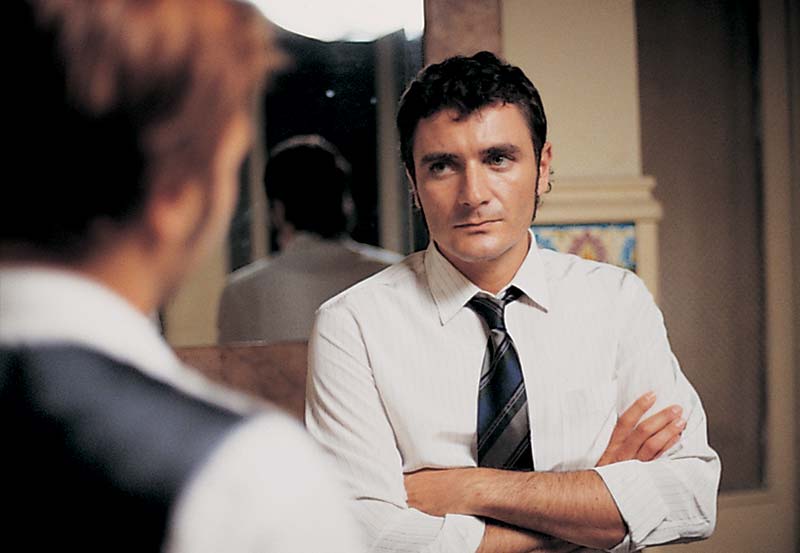

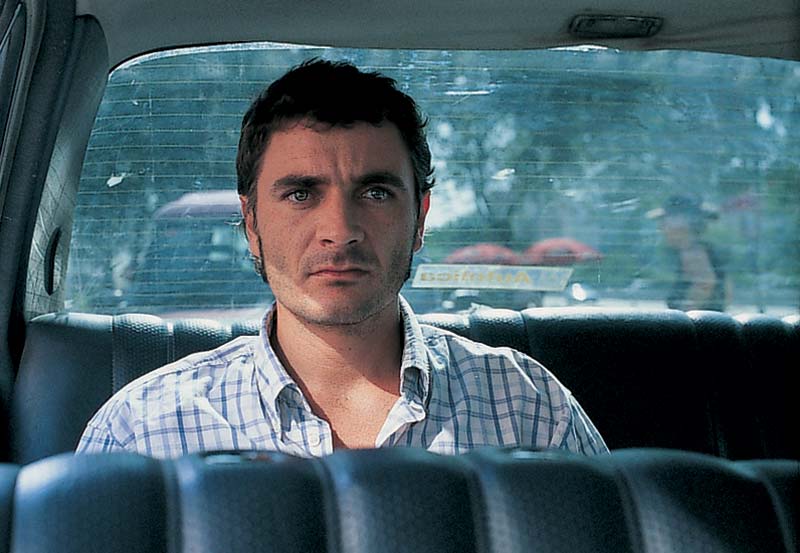

ABEL: Alex Brendemühl

TERE: Ágata Roca

MADRE: María Antonia Martínez

TRINI: Pape Monsoriu

MARCOS: Vicente Romero

CARMEN: Irene Belza

MARÍA: Anna Sahun

TAXI DRIVER: Isabel Rocati

SENIOR MAN: Armando Aguirre

Director: Jaime Rosales

Script: Jaime Rosales, Enric Rufas

Producers: Jaime Rosales, Ricard Figueras

Associate Producer: José María de Orbe

Cameraman: Óscar Durán

Art Director: Leo Casamitjana

Casting Director: Pep Armengol

Sound Recordist: Eva Valiño

Editor: Nino Martínez

Sound Editor: Maite Rivera

1st Assistant Director: Alex Vila

Location Manager: Ismael Glück

Marketing Director: Salvi García

OFICIAL TRAILER

"In 'The Hours of the Day', one sees what one doesn’t see in other films, and one doesn’t see what one usually does"

Director's notes

Jaime Rosales

"The cinematographic creator has honestly fulfilled when, through a painting of authentic social relations, destroying the conventional functions on the naturalness of our relations, he breaks the optimism of the bourgeois world and forces the reader to doubt the perenniality of the existing order, even of something. We do not directly point to a conclusion, including something that does not seem to be an ostensible part of it."

Luis Buñuel

Las horas del día (The Hours of the Day) is an unusual films. It does not belong to any particular genre or tradition, nor does it offer an innovative aesthetic style or a complex narrative structure. It is a simple, direct, and transparent film. And yet, it is different from everything one usually sees. Because in Las horas del día (The Hours of the Day), one sees what one doesn’t see in other films, and one doesn’t see what one usually does.

Based on a realistic aesthetic style, and a a very personal view of everyday life, it offers a disturbing reflection on a phenomenon that terrifies us, and that unfortunately also portrays us we are.

Interview

Freedom, trouth, respect.

Hacia un cine iconoclasta, contradictorio e inacabado.

How did the story for The Hours of the Day come about?

In 1998, I wrote a short film about a man who kills a taxi driver in a empty field and then picks up a prostitute. The idea was to create a piece full of suspense built around the tension the viewer felt, knowing the prostitute was in the taxi with a murderer. Then I thought, “What happens next?” Then I thought there might be a feature film behind it. At the time, I came across an article about serial killers that I found very interesting. I was no longer interested in suspense, but instead in creating a super-realist portrait open to various interpretations.

This is your first film and you are also the co-producers. What difficulties have you had?

Let’s say that playing that double role sets you up for getting hit with the problems faced by both directors and producers. As the director, I’ve had problems concerning the artistic and creative aspects. As a producer, the biggest problem is convincing people with money to invest in such a personal project with such an unpredictable outcome. It’s fairly exhausting. Of course, everything has its good side. The good side is that I managed to avoid the problems between the director and the producer. Problems relating to trust and respect for the work.

How did you do the casting?

I don’t like using actors to create characters. I’m not interested in having actors put together a character that exceeds the actor’s own personal characteristics. That’s just fine in the theatre, but I find it terribly false in the cinema. What I do is look for an actor whose personal characteristics are like those of the character. Then, during the audition, I pay close attention to what the actor or actress is like. If I like them, if I see something interesting even if, a priori, it’s not what I had in mind for the character, I don’t have any difficulty changing the character to make it more similar to the actor.

What is the character, Abel, like?

I don’t know… I don’t really know what my characters are like. While I’m writing the screenplay, I try to listen to what they say to me, and assimilate what they want, and what they do. I try to let them lead me along. What happens is that during that process, the characters don’t tell me everything- they keep some things to themselves. That’s why there are lots of things I don’t know. When I started rehearsals with Álex Brendemühl, I told him there were things I didn’t know about Abel and couldn’t tell him. He didn’t care. The same thing happened with the others actors. I think you have to use your intuition, your instincts. Some analysis is good, but too much can kill your instincts.

The murders are really shocking. Why do you think they cause that effect?

We tried to set up and portray the murders in keeping with the tone of the rest of the film, not emphasizing anything in particular: not the violence or the setting. When I thought of Abel, I didn’t think on a especially able or implacable murderer. I thought, “Killing someone must be very difficult.” First, it’s not something you learn at school or that you practice much, so the technique can’t look very refined. Also, people cling to life and I don’t think they die very easily. We see that in documentaries about the animal kingdom. It’s not easy even for a lion to kill a deer. So that’s how I envisioned the murders. Naturally, the way I imagine they happen in reality, not in the formulaic way movies have accustomed us to see.

The locations, sound, etc., are natural. Was that realism intentional or was it due to the low budget?

Well, both, I’d say. I have a personal preference for realism. I really like Italian Neo-Realism, and the aesthetics of documentary filmmaking in general. Is one aims to maintain a certain artistic freedom, which for me means being able to say what one wants freely in the personal way one wants outside of what sells, what people are interested in, or what entertains, then one must face the fact that one won’t have many means to work with. Realism, in this sense, is a cheap that makes a lot of things easier. Except the small difficulty of recording live sound, everything else regarding realism seems to be an advantage.

The film has no music. Is the lack of music part of that realism?

Yes, but that’s not the only reason. Aside from the demands of realism, in my case, I don’t use music because I don’t think music is intrinsic to the language of cinema. Unless there is music in the scene itself, such as in a bar, it seems like an artificial addition to me. Something that is used all the time, and to good effect, but it is inappropriate. Using it seems to make up for something lacking in the setting. It’s a sort of trick used to emphasize an emotion in the viewer. I don’t want to emphasize anything.

There are questions left unanswered in the film. Is that intentional?

For me, making a film is setting up a dialogue with the viewer. A dialogue between equals. In order for a dialogue to take place, both sides have to participate. Otherwise, it’s a monologue. It’s not a matter of trying to shock or idolize the viewer. For me, making a film is offering a way to the viewer. Leaving the interpretation open for the viewer to make, bringing his or her own sensibility to it. This does not mean falling into indecisiveness. Quite the contrary, it means creating something tremendously concrete that also leaves some open doors.

What are your artistic preference? What kind of cinema do you like? What aesthetic style are you closest to?

As I told you earlier, I am a great admirer of Italian Neo-Realism. It is an essential reference point for me. I also find what happened in the Nouvelle Vague very interesting, especially Godard. In his films, he questions what cinema is by making cinema. I fins that fascinating. He opened a fundamental path for investigating what modern cinema ought to be. Just as happens in the case of abstract painting, and post-modern tendencies, cinema also has to ask about its own nature within films.